Warren Piece

by David McGillivray

Will Norman J. Warren’s lifelong friend and collaborator McG be allowed to use this groan-inducing heading?

I shouldn’t have been commissioned to write this appreciation of Norman J. Warren. To be brutally honest, I don’t particularly like his films – including the two that have my name on them.

I’m not alone in this respect. Norman is one of very few film-makers – I’m afraid two of the others are Ed Wood Jr and Andy Milligan – whose biographers emphasise their subject’s shortcomings. In Norman J. Warren: Gentleman of Horror, published last year, foreword writer Alan Jones calls Satan’s Slave “possibly one of the worst films ever made.”

Elsewhere in the book, the authors include comments about Norman’s films made by examiners at the British Board of Film Classification. “This film is so bad, it’s almost funny,” wrote one of them about Gunpowder.

It goes without saying, however, that we would not be giving the Norman J. Warren Award to aspiring horror directors if Warren were as bad a director as Wood and Milligan. We are celebrating his memory not only because he was famously “the nicest man in the business” but because, for every brickbat Norman received, he also got a bouquet. Terror is a typical example. One review on IMDb is headed “Absolute tosh.” But for another reviewer this is “Norman J. Warren’s low-budget classic.”

I’m fairly sure that, when interviewed for extras on the Vinegar Syndrome DVD release of Terror, I pointed out that it is difference of opinion that is a crucial factor in the creation of a cult. The biggest cult movie of all time is Citizen Kane, a box-office failure later acclaimed the best film ever made. So many people argued over whether Welles’s folly deserved this accolade that the rest of us had to see it and a cult was born.

By the same token Norman usually was at the arse-end of the film industry in the 1970s and 80s; his films were recognised by very few and they made him very little money. But then along came a couple of fanzine editors who felt that the films of Norman J. Warren possessed something noteworthy. They were re-released on home formats and another cult took shape. It was developed in part by Norman himself. His relatively big-budget sci-fi shocker, Inseminoid, had not encouraged all-expenses-paid trips to meet Hollywood producers and all that lay ahead were two poverty row indies that were barely released.

Norman needed to find something else to do.

No discussion of the film career of Norman J. Warren can ignore his second career as a guest at horror film festivals. Perhaps significantly it endured around ten years longer than his twenty-year stint as a director.

No discussion of the film career of Norman J. Warren can ignore his second career as a guest at horror film festivals. Perhaps significantly it endured around ten years longer than his twenty-year stint as a director.

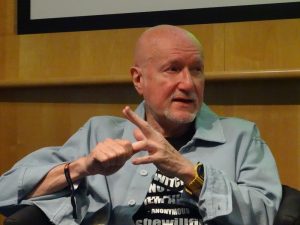

Norman was one of the best-known of the film-makers that accepted every invitation and endeared himself to a new generation of fans by being charming, funny and happy to talk sometimes into the early hours even to the most clammy-handed obsessive. He promoted his films to people who discovered in them aspects that frankly had always been there: enthusiasm and indeed love for all forms of cinema; particular admiration for the William Castle and Roger Corman schools of exploitation; and, yes, a capability that raised most of his films above the level of shlock.

They may not be for everyone. But more importantly the Festival has chosen to name a new award after a friend so well-loved by all that it’s inconceivable anyone could have an objection. This is why Norman J. Warren is a very special person.